As part of its reconciliatory function, the TRC is also responsible for the granting of amnesty, which means that perpetrators of gross violations of human rights who meet TRC criteria are free from prosecution and all liability then falls away. To receive amnesty, perpetrators must have committed politically-motivated crimes and fully disclosed all the information concerning their actions. At the end of its term of office in March 1998, the TRC will document all of its findings in a comprehensive report, making recommendations aimed at preventing such large-scale abuse from ever occurring again.

To date, the TRC has taken some 10,000 statements from survivors or families of victims of murder, attempted murder, "disappearance" and torture. A number of representative cases have been selected for public hearings based on these statements. Sixty-five such hearings, at which victims have told their stories to the nation, have been held thus far. The TRC has also received a staggering 5,400 amnesty applications. Although time is running out, only 50 findings have been made, of which roughly 70 percent have resulted in situations where perpetrators of gross violations of human rights have been granted amnesty.

In evaluating the process, it is clear that providing space for victims to tell their stories has been of much use. It is the first time that many South Africans have been able to do so to a sympathetic ear. Furthermore, their cases have been referred to the 60-odd national investigators of the TRC Investigation Unit for thorough investigation. In the past, often due to police complicity, most people were turned away from police stations, particularly when their cases were of a political nature.

Despite the success of the hearings, the actual psychological impact of giving public voice to trauma has had varying consequences for victims. For some, it has been the final leg of a personal healing journey while for others, it has only been the first step. Throughout the TRC process, there has often been a simplistic assumption that catharsis through telling one's story is sufficient for emotional healing. This is only partially true. For many, although public acknowledgement of their suffering may have restored their dignity and taken away feelings of guilt, psychological healing remains far off and of a highly personalised matter. Such healing usually requires ongoing support from professionals, community groups, relatives and other support structures like religious bodies. The individual follow-up of victims by the TRC has not been as extensive as was hoped. Undoubtedly, the emotional needs of many victims remain insufficiently addressed.

|

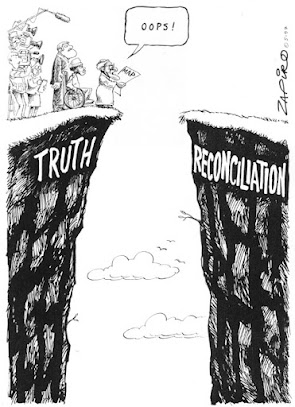

© 1997 - 2022 Zapiro (All Rights Reserved). Originally published in The Sowetan in 1997. Printed/Used with permission. More Zapiro cartoons at www.zapiro.com |

Regarding reparations or compensation for victims, the TRC is only responsible for drawing up policy as reparations will be steered by the government following the TRC-mandated period. The hearings have revealed that the needs of survivors and families of victims are varied. Some people simply want a tombstone to commemorate the death of a loved one, others want financial assistance due to the loss of a bread winner, while some demand that the perpetrator be punished. On a psychological level, reparations can serve for survivors as a symbol representing that they have come to terms with a trauma. On a purely practical level though, the sheer number of victims needing reparation makes the idea of individualised reparation difficult to imagine. Nonetheless, the government remains obligated to offer victims some form of compensation for their suffering because the granting of amnesty to perpetrators has denied victims the possibility of a civil claim.

In addition to possibly offering individualised reparation, the TRC will also make recommendations about symbolic ways of remembering the past. A memorial dedicated to those who lost their lives fighting against apartheid, perhaps similar to the Vietnam War Memorial, is certainly a possibility.

The amnesty granting function of the TRC remains most controversial. Political analysts argue that amnesty is necessary to ensure a peaceful resolution in South Africa and that large-scale prosecutions are simply not possible given the inefficiencies of the criminal justice system. For survivors and families of victims, it remains difficult to see perpetrators walk free yet the South African model is a significant improvement to that of other countries, though, as amnesty is not automatic or blanket. Perpetrators have to qualify for amnesty, specifically needing to make a full, public confession. This means that for many people, the truth about the past will finally be known.

However, despite the value of knowing the truth as implied by the TRC slogan, truth alone does not always lead to reconciliation. Some victims may be satisfied by knowing the facts, particularly in the case of a "disappearance" but for others, truth may heighten anger and calls for justice rather than leading to feelings of reconciliation. There is also the constant threat of a perpetuated cycle of revenge once the truth is out. Thus, survivors and families of victims need to accept their anger as legitimate without feeling they are expected to forgive perpetrators. Community-based groups provide some victim support as outlets for frustrations. In contrast, the TRC has at times failed to provide adequate space for victims to vent their anger.

Even if the compromise of amnesty had to be made for pragmatic reasons, the TRC has failed to make it explicit that the Commission is of the opinion that it was an "evil" compromise. This may have devastating effects. It can leave victims feeling that the TRC favours perpetrators over themselves. This perception is further heightened by the sense that at present it appears as though perpetrators have more to gain by receiving amnesty than victims have through reparation. Reparation seems distant as it will only occur once the TRC is over and their is no guarantee of what form it will take. A further problem is that no matter what form of reparation is offered, it can never bring back a loved one. Coming to terms with the past psychologically can only in part be addressed by a reparations policy.

The road to reconciliation in South Africa remains a thorny one. Undoubtedly, the TRC has helped smooth the path. The value of publicly revisiting the sad and brutal days of apartheid has opened the eyes of many, having partially developed a collective history for South Africans and allowed victims to evolve a new meaning for their suffering. However, individual processes of forgiveness and reconciliation may not always intersect with the collective process offered by the TRC at this time.

It is a mistake to assume that storytelling equates with healing and that truth alone will lead to reconciliation. Truth does not ensure transformation. Much work remains to be done to actively engage with the offending institutions like the security forces to secure lasting change. Simply knowing the truth is no guarantee that a human rights culture will permeate their future operations. Perhaps most basically, the new government has the difficulty of delivering real economic change because all the truth in the world will never address the multiple effects and miseries created by ongoing poverty.

This article was published in Cantilevers: Building Bridges for Peace, Vol. 3, 1997. At the time, Brandon Hamber was the Manager of the Transition and Reconciliation Unit at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation.