Review on an Exhibition by Clifford Charles and Samson Mnisi

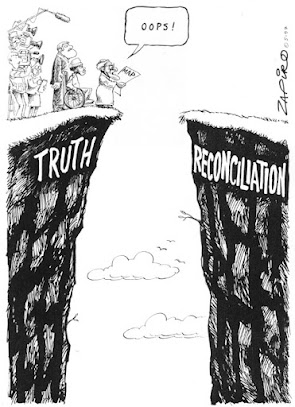

The South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission has breathed life into an ever present yet often concealed reality of decades of repression and violence. As a result all South Africans are confronted daily with having to integrate a troubled past and violent present into their own personal narratives. The Black in Town exhibition at Number 11 Diagonal Street externalises one such narrative or personal journey. For me, this journey (which is implicit in the work), starts with a graphic piece shaped around a blood-stained TPA Baragwanath blanket that was used by Samson Mnisi, one of the artists, when he was shot. From there, the display moves through the corporate office space where it is housed, embodying all the ambivalence of the old and the new, the healing and the damage and the visible and the hidden in South Africa.In my opinion, the so-called reconciliation process taking place in South Africa is an inherently contradictory one. This contradiction is most present in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission which demands a necessary scrutiny of the past so that healing can occur but at the same time defines the safe parameters within which this can happen. Thus, to some degree, denying personalised elements of healing and ritual. Similarly, the exhibition is housed within the boundaries of corporate South Africa on the 13th floor of a modern office block that overlooks the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. This captures the complexity required in having to heal past wounds within old spaces - spaces that cannot be torn down yet remain laden with destructive wishes and painful memories. As the exhibition weaves intricate patterns of the past and present and differing ways of healing wounds, so too the traders whose stalls surround the Stock Exchange are constant reminders of a new South Africa that is pregnant with irony, concealed oppression and both positive and negative change.

Most of the pieces in the work consist of rich layers of material often coated with wax. These layers upon layers of material peppered with intricate markings and scratches capture the complex nature of psychological healing. Always present in any healing process is the internal tension between the will to uncover and deal with painful memories and the human desire to cover-up and try and forget. At times, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission has forced the belief that it is better to uncover the truth and relive the pain at all costs. In contrast, the exhibition Black in Town, in my opinion, captures more of the ambivalence and depth of the healing process. This is reinforced by the highly personalised markings on all the pieces that point to the individual nature of psychological restoration.

The array of perplexing work is marked with religious and other symbols, smells in different rooms and the use of music and varying materials. For me the exhibition captures the essence of psychological healing, a process that is always laden with an integration of elements we all carry through an ever changing culture and from generation to generation. It demonstrates a personal journey that transcends politics, texts and institutions like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission that have been created to facilitate memory and rehabilitation. Like a scar, a scab or a band-aid - all fraught with complex images of their relationship to healing - the exhibition Black in Town captures the realistic contradictions of healing wounds in a South Africa in transition.

Published by Brandon Hamber who is the former Manager of the Transition and Reconciliation Unit at the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation Commission.